Will Syrian survive the Civil War?

The wave of revolutionary popular protest movements that swept across the Arab world in the year 2011, commonly known as the Arab Spring, was quite late to arrive in Syria. When it did, however, it took a form more violent and disruptive than anywhere in the Arab world. The country was in the midst of a full-fledged civil war within a year-and-a-half of the first demonstrations. The fighting grew ever more intense, and the underlying political landscape ever more complex, to the point that several major foreign actors got involved and dozens of armed groups gained control of varying amounts of territory and resources all around the country.

Ten years later, there are no signs of the crisis coming to an end. I would argue that a solution based on unification is indeed unrealistic at this point. Instead, a negotiated or informal settlement might well be the only remaining way to bring this bloody conflict to a conclusion.

A Violent Outbreak

When the Arab Spring first began to take over large parts of the Arab world in early-2011, the official Syrian media apparatus was confident that the unrest would not reach the country, for the people were supposedly satisfied with the performance of the Ba’ath party dictatorship. It turns out that the narrative was overly optimistic about the Assad regime. Major protests erupted in the capital itself as early as March. They were met with an overwhelmingly violent reaction on part of the law enforcement.

It was not long before the opposition began to arm itself, mostly under the broad banner of the Free Syrian Army coalition which defined itself by its opposition to the Ba’ath dictatorship. President Assad now began to claim that the protests were the result of a join American-Israeli conspiracy against the Party, and must be dealt with an iron hand. Quite predictably, open fighting erupted in several locations in summer, and large parts of the country were firmly under opposition control within a year.1

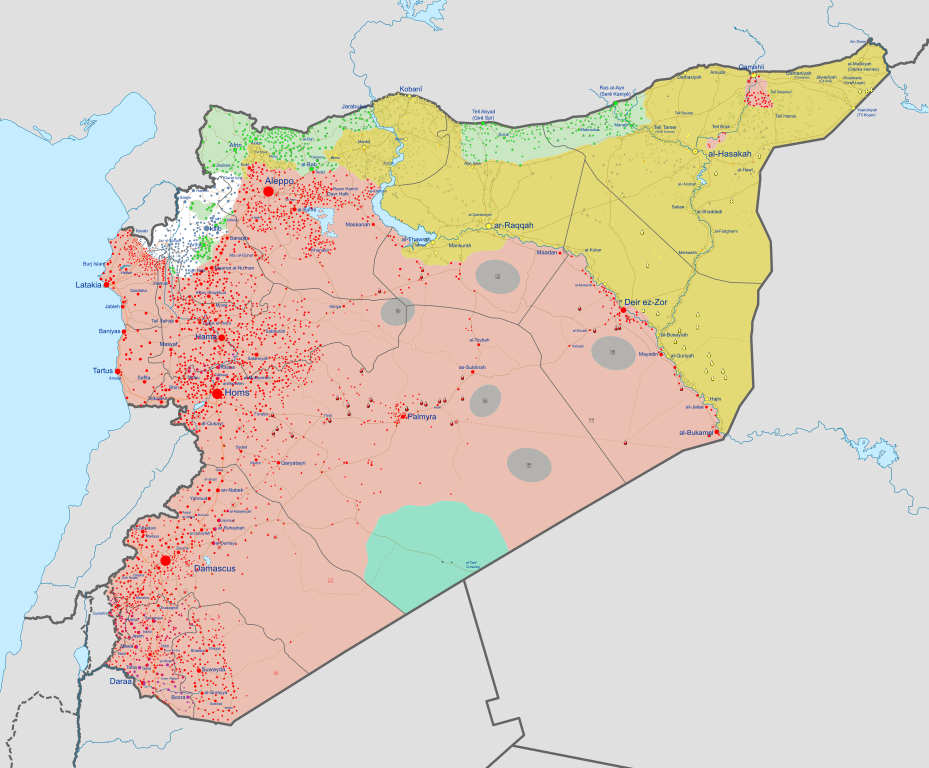

The fighting, as we shall see, gradually became more and more complex as new actors emerged. What is clear, however, is the devastating scale of the conflict. Within four years, the Syrian Civil War had already produced the largest refugee crisis in history. The country has been effectively divided into dozens of parts at times. As of 2021, however, only three of these rival governments seem likely to survive in the long run.

Major Actors

The most powerful and influential actor in Syria is still the Bashar al-Assad government based in Damascus. The one-party dictatorship continues to face staunch opposition on its own territory outside a hard-core region in the West. However, this is more than offset by the enormous foreign support that the regime enjoys. It is, in fact, the large amount of economic, military and political assistance from Iran and Russia that has provided a lifeline to this despotic regime for decades. Both Iran and Russia retain a strong direct and indirect presence in the government-held parts of the country.

The second part of the country which is very much autonomous and stable is Rojava. Rojava forms the southwestern part of the historic region of Kurdistan and holds most of Syria’s natural wealth. Its political leadership and military forces, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), retains close ties to the West. The SDF received extensive direct support from the West in its early stages. The United States, particular, contributed greatly to the SDF’s fight against the so-called ‘Islamic State’ (or ISIS). The U.S. still retains a military base in eastern Syria, although its direct presence in Rojava ended in early-2019.2

The third key actor in Syrian civil war is the Republic of Turkey and armed groups sponsored by the nation. Turkey has been directly involved in Syria from the beginning, but its activities have escalated dramatically since 2016. In fact, it is the only foreign nation to undertake overt ground military operations on Syrian sovereign territory. The Turkish interests in Syria do not align perfectly with either the Kremlin or its NATO allies. Instead, they stem primarily from its concerns about internal security and large-scale immigration. As a result, both ISIS and the Kurdish militia of Rojava are perceived as a threat. Turkey controls a considerable part of northern Syria through its allies, primarily the Syrian National Army (SNA).

The fourth and final actor that once occupied large parts of the country is the ISIS. A universally-recognised terrorist organisation, the Islamic State failed to consolidate its gains in Syria due to its extremist policies. However, many ISIS- and al-Qaeda-affiliated groups do maintain a strong presence. Unfortunately, the possibility of their eventual revival cannot be completely dismissed thus far. For now, however, radical Islamists are unlikely to hold any sway on the future of Syria.

Schism within Schism

As we have seen, the Syrian opposition was at first defined by its shared dislike of the al-Assad regime. That vague unity never materialised into a concrete agenda, however. Instead, the opposition is now itself bitterly divided among two broad lines: Ethnic and religious. One the one hand, the ethnic Kurdish groups have largely been unwilling to ally with secular Arabs, while on the other, the predominantly Sunni Arab opposition groups also do not share the SDF or SNA vision of the country. As a result, the original unity behind anti-government sentiments has rapidly dissipated, to the point of bitter infighting. Much like in Iraq, this process has led to the fragmentation and radicalisation of a previously-secular society. The Syria state is now firmly allied with Iran and radical Shi’a movements, while much of the Sunni opposition is based around groups like the ISIS and al-Nusra.3 Furthermore, as one analytical journalist has aptly pointed out,4 the Sunni Arab opposition to al-Assad regime also remains staunchly statist to this day (one reason for this might be the abundance of natural resources in the Kurdish north), which is a huge hindrance to achieving any common understanding with ethnic minorities.

Conclusion; Reunification or Permanent Ceasefire?

If the Syrian Arab Republic is to survive as a single nation, the civil war will eventually have to end in a victory or a compromise. One obvious way in which Syria could be reunited again is through the al-Assad regime itself. One possibility might be an insider coup from a reformist faction, which could potentially persuade the rebels to negotiate. One might also argue that the Damascus government could eventually overcome the opposition militarily, probably with heavy Russo-Iranian support. Both of these, however, are extremely unlikely at this point.5

A more realistic way for peace in Syria, at least in the near future, would be a negotiated compromise.6 Even if a formal agreement is not reached, however, relations between the competing government and opposition groups (or coalitions) will likely normalise over time. In the end, it is probably too early to predict what the final solution to the Syrian Civil War would be, a conflict which has already lasted for over a decade with no end in sight. More likely than not, the Syrian Republic might simply never become a single, unified country again. If so, it will only be sharing the fate of the Congo, Columbia, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, and countless other post-colonial nation-states torn by perennial internal tensions.

Leave a reply